Agriculture – The Source of Life

If I were to define agriculture in two words, I would say it is the source of life. It is the source of life because it is the source of food and is increasingly becoming the source of energy. It is the common bond of our humanity that unites us and places demands upon us. Jawaharial Nehru once said ”Everything else can wait, but not agriculture“ .

Recall that at the dawn of the 20th century there were but 1.5 billion people on earth and now in the first decade of the 21st century we number over 6 billion and moving up to around 9 billion by mid century 2050.

To meet the needs of our vast human family will require new approaches that recognize in today’s world that no country is an island complete unto itself.

We know that mother earth has been ravaged down the centuries and vast areas of land rendered barren and that, coupled with the pollution and overuse of water systems, demands that we think again on how we will preserve, nurture and use wisely the very means of our survival.

And as if feeding our very large human family wasn’t challenge enough, we are now embarking at breakneck speed to also require from the same ingredients of land, water and sun, the production of even larger volumes of bio fuels.

It is right to say this is a challenge. It is very much more, for to succeed will require leaders to make quantum shifts in existing policies, to make tougher decisions than they have ever made before, to tune the pleas for more protection and support from the rich world and to open their ears to the pleas for just access to capital, resources and markets from the poor.

In recent decades the seductive allure of the wonders of science, the communication revolution, the excitement of money markets, concern about the diminishing supply of fossil fuels and numerous other issues have distracted the minds of many from the centrality of land, water and agriculture in all its forms to our survival.

No longer. Agriculture and the wise stewardship of land and water have moved to the forefront of attention in the international community because you can’t debate the world’s number one issue, global warming and climate change without acknowledging the central role of agriculture.

Think of it as a new global revolution that will demand much of many.

The new market for bio-fuels is a potential boon for many farmers but it likewise will lift the cost of food to consumers rich and poor alike.

Today’s revolution is much more challenging and important than the Green Revolution of the 60s. We not only have to grow more food but must also have concern for the methane gas, that emerges from rotting vegetation in the vast rice paddies and from livestock all over the world.

The world is still at an early stage of developing even the conceptual frame work that will bring all the elements of managing the competing demands into sustainable policy. Inevitably that policy will rely on science to make the necessary breakthroughs in a range of areas.

It is a very complex task and no earlier generation faced such demands, but a committed world can meet all these goals if we have the will.

To make the progress needed will require new entrepreneurial thinking, new partnerships, joint ventures and building new relationships as all sectors of the agri-food chain must act together to promote sustainable development.

Further, for farmers to succeed they must have access to markets. While at first they may supply only local or domestic markets, they of necessity need to have fair access to the global market place.

Unfortunately world trade in food is still the most distorted and unreformed of any market. The Doha round of world trade talks on improving global access for agriculture is still stuck in old arguments on who should move first and by how much. It is not the poor and impoverished that are holding back, it is the big, powerful and rich nations that want to retain their subsidies and barriers.

Political leaders with global responsibilities however must hear and walk to the beat of a different drum.

What a transformation that would bring the world’s outlook if the young and restless in thousands and thousands of huts and villages and cities across the globe knew that the world was opening up opportunities to them. That they by the application of their individual or collective effort can go out and make a better life for themselves and their families.

Creating prosperity is always a challenge for many reasons. Creating prosperity from agriculture is an even greater challenge because it involves overcoming increasingly serious resource constraints without diminishing our capacity to produce nutritious food and fiber that continues to grow as the global population grows.

Meeting these needs will require us to double food production over the next four decades. Just imagine – on top of our need now to improve diets for over two billion new people – we will need to feed 2.5 billion new people - almost another India and China. Those tasks alone are quite a tall order indeed for global agriculture, one thought impossible not too long ago.

This new and growing demand-component reflects global economic growth and its capacity to change the economic profile of large developing countries - dramatically. Growth in these economies has been, and likely will continue to be more than twice as fast as in developed countries. Such trends have extremely important implications for agriculture because they support the growth of emerging middle-class consumers on many continents of the world who not only can increase food consumption, but can improve diets as well. These trends are expected to continue for the foreseeable future. Meeting these demands implies the use of far more agricultural resources if current economic levels continued.

But while the challenge of producing food for growing markets remains, an additional challenge reflects the fact that agriculture is also providing pathways to both cleaner air and energy diversification. These ideas have taken hold at an astonishing pace in response to higher energy costs, and to growing evidence of climate change. Already, a new, strong and rapidly growing market has emerged in several parts of the world, with its effects now noted everywhere.

Today, Brazil utilizes just over one-half of the sugarcane output from 7.2 million hectares to produce some 20.5 billion liters of ethanol. And, it offers both the plans and capacity for significant expansion.

The EU already has some 120 biodiesel plants in production with an annual capacity of over 6 million tons. Still, this growth is just the beginning. It now has a biofuel target of 5.75% of fuel use – a level that will require output to quadruple and use more than 15% of the arable land base for fuel production.

There are now biofuel programs in Japan, China, India, Indonesia and elsewhere throughout Asia. Significant biodiesel production already exists in several locations, and some are now exporters. More capacity is being constructed, and still more planned as more and more Asian government mandates are approved.

In the USA ethanol output continues to expand dramatically. Output already fast approaches the 7.5 billion gallon target set for 2012. It is expected that corn to be used for ethanol in 2007 is approaching one-fourth of the entire output. Some experts suggest ethanol output could exceed 16 billion gallons by 2015 and utilize 40% of a greatly expanded annual corn output.

And, the story is similar all across the world - biofuel production is beginning, expansion is underway, and much research is being devoted to exploration of a wider array of potentially more efficient feedstock.

These visions of both greater energy diversity and cleaner fuel are increasingly confronting real, immediate constraints: Arable land is scare; competition for water is growing; and capital has many competing uses. And, we must be evermore concerned about agriculture’s impact on the environment while simultaneously developing practices which foster sustainability.

As we ramp up the use of agricultural resources for both food and fuel, there is growing recognition of environmental degradation across much of the world. Agriculture has been an important player in efforts to reduce soil erosion, improve water and air quality, and enhance wildlife habitat. Ameliorating these problems while increasing cropping intensity will continue to require new technologies, added investment, and new farming practices. And, now the problem of climate change creates impetus for all industries including agriculture, to reduce the size of their carbon emission.

Clearly, the challenges that now confront our world link agriculture, food abundance and prosperity and are underlain by the additional challenge of rapid change. How do we provide the additional products needed from the land – growing volumes over time with ever-increasing quality expectations – even through resource constraints become more pressing while issues of environmental quality and sustainability assume higher priorities?

We know that change increasingly will be required to meet the growing needs of the future. In fact, we probably cannot meet our goals with existing constraints.

We may need to “revolutionize the global system” and in many respects this is already under-way.

This is not an unprecedented circumstance, in historical terms. It is instructive to remember that only a few decades ago the specter of famine often stalked India – and many other nations, as well. The Green Revolution was a technology-based answer to a series of challenges, a still-compelling demonstration of science and capital applied to human needs. And not too long ago,the theme of “Who will feed China?” was a very real concern. By altering incentives for technological innovation and by accepting greater economic openness, Chinese policy changes have enabled significant progress. Agriculture has not lost its capacity to meet such challenges, and it can help meet future energy needs as it once mobilized to provide food.

But, it is clear that achieving greater prosperity while addressing growing societal problems will require sustained and sustainable economic expansion. By now, the basic recipe for economic development is generally known. The necessary ingredients are familiar even though their assembly and actual application almost always proves difficult. The essential aspects will include:

The “right” mix of economic policies and regulations to create an environment conducive to business meeting customers’ needs, and to business investment for the good of society. That means transparent systems and free flow of capital and information. History is replete with illustrations that affirm the close correspondence of these conditions with rapid and sustained economic growth.

Technological innovation is the time-tested foundation for success in avoiding the “resource limits”. Meeting the challenges before us will require further technological breakthroughs, to be sure. Experience has shown that when these conditions occur, investors are attracted and the requisite capital for productive facilities and infrastructure materializes, accompanied by advanced technology and management practices.

In this vision, a proper business setting will provide sufficient incentives for rapid technological advancements (for renewable fuels, for example). It also will help us become more efficient and better utilize the resources we already have and to mobilize the capital needed for infrastructure development. Such a setting will provide the economic incentives the global agriculture system needs to be able to meet the 21st century needs for food, fiber, and fuel more fully and in a more sustainable way than it mobilized to meet 20th century needs for food and fiber.

This then leads me to suggest that our aspirations should be even greater than they are. “Creating prosperity” means going beyond just minimally meeting food and fuel needs- “creating prosperity” is a big step up from just avoiding famine. The concept implies the potential for more people to actually “ enjoy prosperity” than ever before. Of the 6.5 billion people in the word today, some 1.25 billion live on less than $1 per day and 850 million (67%) of those are malnourished and hungry. A total of 3 billion live on less than 2$ per day. Embedding the “right” mix of policy and regulations will enable appropriate investment in agriculture to improve incomes for hundreds of millions in rural areas. And, a more efficient, fully functioning food system will benefit hundreds of millions more in the vast urban centers that will see higher quality, less expensive food.

Since we know what to do and how to do it, what more is required for progress that is both tangible and soon? One still missing element is the political resolve to create and embed the conditions necessary to enable the system to respond. There must be a strong exertion of “political will” to assemble the ingredients and apply the process – and, hereby create the political and economic conditions that can attract the capital investment, facilitate the unimpeded flow of technology and information, and empower local entrepreneurs.

This “political will” must be national in the many countries whose economies remain largely isolated with internal artificial incentives and disincentives that restrict modernization and progress. Sad to say, these often are the very countries most in need of progress but also the most difficult to reform.

But, “political will” must be exerted elsewhere as well, such as in the capitals of some developed countries where, for example, tough decisions are now required to bring the long-stalled multilateral trade negotiations to a successful conclusion. Global agriculture would benefit enormously from a new WTO agreement and the biggest beneficiaries would be developing countries. Not only would they gain from greater access to developed country markets, but highly beneficial south-south trade also would be facilitated.

Perhaps the best hope is that politicians and other leaders realize that the opportunity now exists to utilize agriculture as a powerful engine for faster and sustainable economic development – with the potential for achieving significant reductions in poverty, diversified energy sources, improvements in diets and rapid jumps in living standards for literally billions of people. Because products from the land are in great demand, many are willing to mobilize the capital and develop the technology to help meet that demand, and to do so in socially responsible ways. But, there must be an accommodating, transparent, stable business climate in which to operate.

We can mobilize global agriculture to meet these needs, and do so on a sustainable basis. And, because of the world’s interest in renewable fuels, we can achieve even more – we can improve global prosperity in the process. To do so, we must create the conditions that provide incentives sufficient to mobilize capital and advance the technology taking account of the environmental and other social concerns.

Certain statistics and facts might shed light on appropriate solutions to the above mentioned challenges:

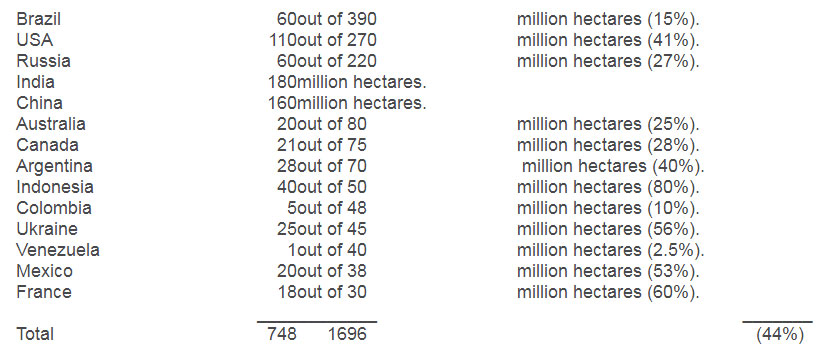

The rural population of the world is now stagnating at 3.2 billion and will likely decrease by 2050 to 3 billion. On the other hand, the urban population is steadily increasing from 2.7 billion in 2000 and is likely to hit 6 billion by 2050. The percentage urban population is now 80% in North America, 75% in Latin America, 72% in Europe, 40% in Asia and Africa. Utilization of arable land in the major agricultural countries of the world are:

While world population increased from 3 billion in’ 1960 to 6.5 billion in 2006, the agricultural area increased only from 4.5 to 5 billion hectares during this same period.

During the coming four decades, the per capita annual income growth will most likely stagnante at 2% in the developed countries, 5% in Asia, 4% in the ex-communist countries, 3% in Latin America and the Arab countries, and 0.5% in Sub-Saharan Africa.

During the first five decades of this century, the per capita food consumption per day will increase from 3400 to 3500 Kcal in the developed countries, from 2800 to 3300 in East Asia, Latin America, Ex-communist countries and the Arab Countries, from 2400 to 3000 in South Asia, and from 2200 to 2800 in Sub-saharan Africa.

The world yearly per capita food consumption during the first five decades of the 21st century will change from 165 to 160 kgs of cereals, from 70 to 75 kgs of roots and tubers, from 22 to 28 kgs of sugar, from 12 to 18 kgs of vegetable oils and oil seeds, from 35 to 52 kgs of meat, from 78 to 100 kgs of dairy products.

Renewable fresh water resources are 44000 billion cubic meters per year distributed at 31% in Latin America, 27% in Asia, 15% in Europe, 14% in North America, 9% in Africa and 4% in Oceania.

Note, however, the wide variance of the use of this water between developing and industrial countries. Agriculture uses 82% of available water in the developing and under developed countries vs 30% in the industrialized countries. Industry uses 11% of available water in the former vs 59% in the industrialized countries. Domestic use is 8% vs 11%. In 2005 GMO planted areas have reached 47 million hectares in the USA, 17 million hectares in Argentina, 10 million hectares in Brazil, 7 million hectares in Canada, and 4 million hectares in China. And this is on a steady increase.

World carbon dioxide yearly emissions has reached 43000 million metric tons, 28000 million tons of which are emitted by energy consumption. These are generated 35% in Asia and Oceania, 25% in North America, 17% in Europe, 10% in Eurasia, 5% in the Middle East and 4% each in Africa and Central and South America.

Ethanol production is planned to increase from 30 billion liters in 2000 to 114 billion liters in 2012.

Biodiesel consumption is planned to increase from 3.8 billion liters in 2004 to 50 billion liters in 2012. The USA, being the largest corn producer in the world, will increase its annual use of corn to fuel from 75 to 110 million tons, to animal feed to remain at 150 million tons, to exports from 50 to 60 million tons and to domestic use to remain at 35 million tons.

The EU has launched a biofuels program aimed at promoting biomass use whose origin is plant and animal raw material destined for non-food use such as flax, rape, chicory, beetroot, perennial grasses, forestry residues, manure and agro-alimentary industry waste.

The USA has launched a renewable diesel fuel production project based on converting fat from beef, pork and poultry to diesel.

A large scale project is underway to encourage African countries to plant Jatropha shrub whose seeds contain 34% oil which only after filtering can be directly used like diesel fuel.

What can we conclude from the above facts and figures?

Thomas Maltus was wrong 250 years ago relating lack of enough food production to population growth. During the past 40 years food production surpassed population growth by far. World population increased by 93% while increase in various food categories reached 122% for cereals and oil seeds, 287% for vegetables, 47% for roots and tubers, 150% for fruits, 36% for pulses, 73% for milk, 219% for meats, 182% for fish and sea food and 268% for hen eggs. All of this happened with technological advancements.

Besides being scarce and without substitutes, water resources are not well distributed with huge disparities between them and population distribution. Africa and Asia that have 36% of fresh water resources shall concentrate most of future population growth. Therefore we need to boost water consciousness to achieve better water management, recycling, improving irrigation methods etc… We need to encourage rain fed agriculture. We also need to move from water use to water efficiency to water productivity.

World daily per capita income will increase from $14 in 2000 to $20 in 2017, with the developed countries from $77 to $108 and the developing from $4 to $8. This will prompt fast urbanization, changing food habits and booming consumption in the developing countries. It will prompt concerns on healthy eating, food safety, convenience, traceability and good practices in the developed countries.

Increased production and use of alternative renewable fuel will reduce CO2 emission and correct global warming. There is nearly 1000 million hectares of arable land that can be planted in the major agricultural countries of the world for food, fiber and fuel production.

Can a new Green Revolution emerge in order to revitalize agriculture and meet all those aspirations? Yes it can and it must. However this time the private sector all over the world is to do all the work based on clear incentives from governments assured by long term legislated commitments. The private sector can and will delve in assuming the most difficult responsibilities once his path is clear from obstacles and his efforts render him financial remunerations. Therefore the first principle to be applied in achieving our ultimate goal is the “interest of the people”. Unless governments weave their regulations based on the interest of all segments of their societies equally including all those involved in agriculture, progress is unlikely to materialize and the economies of such countries will lag behind.

The USA and EU have long understood such a principle. They have either protected or subsidized their farmers to keep them laboring but with enthusiasm and joy in order to achieve the countries supreme policies of food security, innovation, improved productivity, food safety, reduced costs and environment protection.

They have recently entrusted them in assuming the implementation of alternative fuel production through financing and lucrative incentives.

In the USA, five year firm Farm Bills are revisited for the purpose of insuring a fair treatment and return to farmers while achieving the new set goals. Agricultural subsidies and support measures have exceeded $ 180 billion annually.

In the EU the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) , which was established 40 years ago has been continually revised and increased to reach 50 billion Euros a year.

Both USA, and EU stand firm in justifying their agricultural support policies which in broad terms are:

Ensuring stable supply of affordable and safe food for their population.

Providing a reasonable standard of living for their farmers, while allowing the agriculture industry to modernize and develop.

Ensuring that farming can continue in all regions.

Ensuring that the environment is protected.

Providing better animal health and welfare conditions.

Preventing land abandonment and degradation of the rural environment.

Prevention of loss of employment and the decline of the social fabric in the rural areas.

Large as they are, the cost of agricultural subsidies and support measures in the USA and EU do not exceed 0.5% of their GDP. The real problem, however, lies in the under-developed and developing countries where GDP is low and ability to support agriculture is lower.

With this in mind I see no reasonable justification for the developing countries to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) of the United Nations except under its terms. I cannot blame the developed countries from offering subsidies to entice innovation, productivity efficiency and technological advancement. I can, however, blame the developing countries including the Arab World for rushing to join the WTO and rushing to sign free trade bilateral agreements without deep consideration to the interest of their farmers. That is not an invitation to close borders but it is a message to apply available protection measures by the majority of such countries and to apply subsidies by the few capable ones within the developing world, much the same as the USA and EU have been and continue to do.

Agriculture continues to play a dominant role in the economies of various developing countries including Arab countries. In the recent decades, it was witnessed that the share of agriculture to the overall GDP of various countries in the world has been steadily falling. In the developing world, however, there is a large gap between the rate of decline in share of Agriculture GDP and decline in share of workforce in agriculture. Nearly 60 to 65 percent of workforce is still directly engaged in agriculture where share of agriculture GDP has sharply declined from 40 to 20 percent over the past twenty-five years. This calls for immediate attention of policy interventions to improve agriculture-driven rural employment opportunities.

If we look at why certain regions are still lagging behind others, one could conclude that technology is not a serious constraint for them, but complimentary policy support and required investments are lacking. It is pertinent to note here that the levels of investments and rate of capital formation in agriculture have been falling in the last one decade and this has lead to stagnated production and productivity levels.

In spite of rapid strides made by many developing countries in Agriculture and allied activities, providing food security to vast millions of population, the economic condition of the farmers unfortunately has not improved. Due to unprecedented growth in population during the last 50 years and lack of employment opportunities in non-farm sectors to accommodate the growing population, a phenomenally large population continues to be dependant on agriculture, leading to fragmentation of land and substantially lower incomes. Unless the second Green Revolution that we are now talking about leads to improved welfare of the farmers, growth in agriculture cannot be sustained.

The developing countries, including the Arab countries, where a majority of world population lives and a substantial majority of whom are poor, and where three-fourths of the 3 billion people that are likely to be added to the world population in the next 4 decades are going to live, have to find resources for investment in agriculture and rural sectors. Without making substantial investments in technology, infrastructure, education, extension and markets, it will be difficult to enhance the farmers’ incomes. The irony is that, it is not only the farmers in the developing countries are so poor that they cannot invest, even the governments are poor. Nevertheless the investments have to be made as was made in the last 5 decades, despite all constraints.

The first green revolution which was input intensive and which provided the much needed food security for the world had developed a fatigue. So, substantial investments have to be made in soil conservation and eco-technologies. Investments have to be made by governments in R&D for biotechnology, for better seed development and other crucial areas. We have to revisit agricultural education, extension and technology transfer for enhancing the total factor productivity and for increasing the technology use efficiency in wet lands. Investments have to be made in irrigation and in research for better water utilization. We have to protect and improve soil conditions in areas covered by green revolution through transfer of appropriate technologies and by taking steps to prevent the soil from flooding, water logging and other hazards.

The future investments by all the developing countries, including the Arab countries, have to be made for development of rainfed areas, as the dry lands which comprise 60% of global agriculture have to contribute substantially for the future food security. We have to invest extensively in the development of appropriate technologies and quality seed, essentially suitable for dry land agriculture. Water conservation and water use efficiency technologies are key for development of agriculture in dry land areas.

Livestock and Fisheries Sectors have come to contribute very substantially to the Agricultural GDP in various countries. There should be special focus on these sectors and investments have to be made in animal healthcare and down stream processing units. These sectors are major insurance to the farmers during the years of drought.

Last but not least, the developed countries have a major role to play; in the sense, that they can really provide the market access to the farmers of the developing countries and fair terms of trade for their produce.

Lebanon, one of the Arab countries and the developing nations, has been following a negative policy towards agriculture since 1992. The succeeding governments have adopted a policy calling for leaving agriculture to withstand the outside competition or fade away; a policy that has not changed since. Obviously, with the high costs of the various elements of production, agriculture and the agri-food industry is collapsing. This resulted in migration from agriculture or emigration from Lebanon altogether for both people and investors alike. Therefore Lebanon will not participate in the second green revolution but will, by necessity, become a recipient of the products of such a revolution be it food, fiber or bio-fuel. Simply put, a consumer.

In closing let me say that the world will meet the challenges of population growth not only with sufficient food, fiber, feed and bio-fuel, but will improve the quality and safety of these products to the health of people and to their environment. Such a task will be performed by serious nations mainly industrialized and developed but will also be joined by serious developing nations that are blessed by visionary leaderships unlike many underdeveloped or developing ones including most Arab countries and Lebanon in the forefront.

Beirut – July 7, 2007.